Tertulia: Echoes in Eternity

A Polyphonic Labyrinth in the Recoleta Cemetery of Buenos Aires

Nicolás VarchauskyDOI : https://dx.doi.org/10.56698/filigrane.373

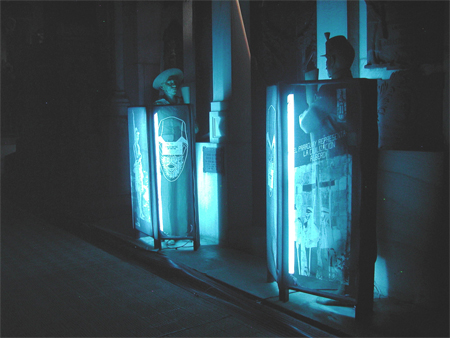

Résumés

Abstract

“Tertulia was a sound-and-image intervention in the Recoleta cemetery in Buenos Aires that I created in 2005 in collaboration with the visual artist Eduardo Molinari. The V. Festival Internacional de Buenos Aires as part of its new interdisciplinary initiative, Proyecto Cruce, produced it. Tertulia’s original three-day program was suspended by court order when some notable neighbours of the cemetery filed a lawsuit that accused us of disturbing the rest of the dead and changing the historic Truth, and called for the project’s cancellation. After the legal confrontation, (in effect, censorship,) Tertulia was rescheduled for the last two days of the festival. On what would have been its opening night, the intervention was canceled due to a fierce storm that started early in the afternoon and lasted the entire night. Tertulia was finally performed on the night of 24 September 2005, after being assailed by the media and the neighbours of the cemetery. The intervention was sabotaged during its only performance: a series of cables were cut, silencing seven of the forty speakers that were spread throughout the cemetery. Five thousand people came to see Tertulia, but for security reasons only 1 500 were allowed into the cemetery.”

Texte intégral

Project

1Tertulia was a sound-and-image intervention in the Recoleta cemetery in Buenos Aires that I created in 2005 in collaboration with the visual artist Eduardo Molinari. The V. Festival Internacional de Buenos Aires as part of its new interdisciplinary initiative, Proyecto Cruce, produced it. Tertulia’s original three-day program was suspended by court order when some notable1 neighbours of the cemetery filed a lawsuit that accused us of disturbing the rest of the dead and changing the historic Truth, and called for the project’s cancellation. After the legal confrontation, (in effect, censorship,) Tertulia was rescheduled for the last two days of the festival. On what would have been its opening night, the intervention was canceled due to a fierce storm that started early in the afternoon and lasted the entire night. Tertulia was finally performed on the night of 24 September 2005, after being assailed by the media and the neighbours of the cemetery. The intervention was sabotaged during its only performance: a series of cables were cut, silencing seven of the forty speakers that were spread throughout the cemetery. Five thousand people came to see Tertulia, but for security reasons only 1 500 were allowed into the cemetery.

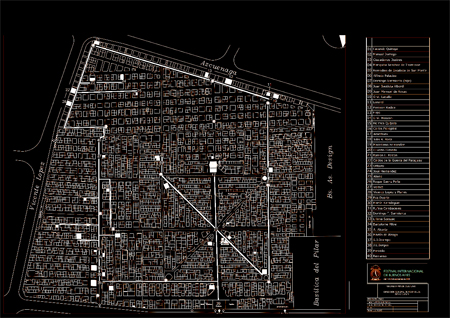

2Between nine pm and midnight, visitors could walk around the barely-lit cemetery and visit the forty tombs that had been chosen as specific sites of intervention from among the 350 000 graves in Recoleta.

Example 1. Cemetery Map

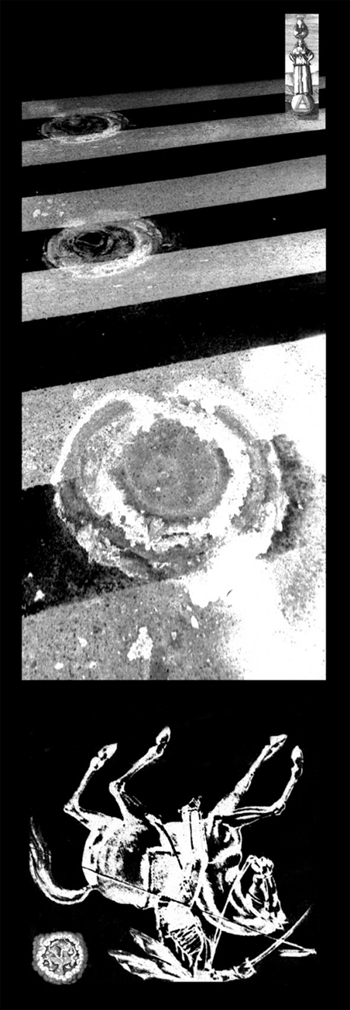

3Installed around each of the forty tombs was a speaker and a black and white image (or a series of images) that referred to the person who had been interred in that tomb. The intervention included over sixty images. Some were made into lightboxes: these were mounted on variously sized black boxes, uniquely shaped to reflect the architecture of their corresponding tombs (Example 2. Falcón’s grave). Others were digitally-printed on transparent fabric; these veils were suspended across the walkways of the cemetery (Example 3. main corridor) or mounted on folding screens, usually surrounding statues (Example 4. Paraguay’s war grave). The audio was played from a spot in the center of the cemetery by two synchronized HD-24 Adat recorders. A unique, three-hour audio stream was composed for each of the forty speakers; the total 120 hours of music was composed using speeches, variations of musical themes (such as patriotic marches or old tangos), and a myriad of sounds.

Example 2. Falcón’s grave

Example 3. Main corridor

Example 4. Paraguay’s war grave

4All of the speakers and images were installed in the perambulatory areas of the cemetery, that is to say, in its public space; though they were very near to the tombs, nothing touched these private spaces in the cemetery. The cemetery is an interesting combination of public and private spaces, for it is operated by the city government and it is open to the public, but each family owns the land and the edifices where their ancestors rest.

5Tertulia required six months of archival research. The national archive (Archivo General de la Nación) was especially important for gathering the images, and the E.T.E.R. archives were a principal source for the project’s sounds.2

6Because of his own work as a visual artist, Eduardo Molinari has immersed himself in the national archives since 2000, when he founded his own Walking Archive (Archivo Caminante). The Walking Archive is interested in the diversity of visual representations of history; it includes documentation of the current state of historic locations and multifarious forms of refuse: flyers, propaganda, old journals and magazines, and the countless types of printed matter people usually discard. Molinari’s conception of walking as an artistic practice brought him to ramble around, camera in hand, looking for traces of the city and country’s history to assemble his archive. In correspondence with Molinari’s practice, an important part of my work consists of developing an archive of street sounds, especially anonymous speech I have recorded in public spaces (such as ambulatory vendors and preachers), ambiences, and the music of amateur musicians performing in the streets.P.A.I.S. Archive3 (Archivo P.A.I.S) is principally concerned with musicality within spoken language and in the sounds produced in public spaces. My work explores these sounds as a structure for musical composition that is based open both to their acoustic and semantic qualities. This coincidence can incorporate – in a musical sense – the subject of enunciation into a musical composition. Following Schaeffer, speech is the only sound that supports causal, semantic, and reduced listening at the same time. Far from casting aside spoken language as a non-musical or essentially semantic material, P.A.I.S. explores speech as a rich source of sounds that are devoid of any reference. When we hear a person speaking, we do not only listen to the meaning of the words, but also to the particular timbre of the voice, its fluctuations and dynamics, accents, melodic gestures, rhythmic patterns, and what Barthes would call its grain4. The referential quality of speech adds a final layer of complexity in which both musical and semantic levels influence each other. The use of different accents, intonations, and timbre modulations can violently change the literal meaning of spoken language, just as the context of an enunciation can modify the way we listen to the musical and non-musical properties of a voice. In fact, we find this to be a more dynamic process in a speaking, rather than a singing voice, (especially if the latter has been trained in lyrical techniques), when the imposition of a musical style has homogenized a voice’s timbre, erased its ‘imperfections’, and modeled its sound to approximate fixed, universalized standards. Lyric vocal technique was originally developed as a technique to sing over the orchestra, to compete with its higher intensity, by reinforcing a formant between 2000 Hz and 3000 Hz, precisely where a slight depression in the global spectral response of an orchestra can be found. In traditional western music, relations of fixed pitch and durations are emphasized over other sound qualities such as timbre, space, or phrasing, especially because pitch and duration are the only relations that this music managed to accurately codify in a score5. But music (at least contemporary music) is actually happening in oral speech. Theatrical performance is more closely related to the concept of music addressed by P.A.I.S., because actors are trained to express many different things (that is, to produce many different sounds) by using a fixed semantic unit. They can build a parallel (musical) speech that, through its use of accents, timbre, dynamics, and intonations, produces another level of meaning within spoken language, which can even contradict its literal meaning. Drawing upon these interests, P.A.I.S. develops its archive and produces musical and interdisciplinary works focused on public spaces, as a way to explore the idea of absolute music6 as the true and real essence of music. In Tertulia, P.A.I.S.’s major work of 2005, further developed the project’s cardinal interests: music within oral speech, public spaces as loci that modify the perception of sound,7 research in sound archives, and a spatially-based conception of music.

Site

7The Recoleta cemetery is the oldest in Buenos Aires. In 1822, the state expropriated a piece of land that belonged to the Recoletos monks’ eighteenth-century colonial convent, today known as Basílica del Pilar, and created the city’s first cemetery in order to meet the demands of its growing population. Through it was initially built as a catholic cemetery, Recoleta has been a secular burial ground since the end of the nineteenth century, when its holiness was purportedly compromised by the interment of masons within its confines. Most of the important figures in Argentinean history rest in the cemetery, and many families of the aristocracy have their tombs there.

8Located in a very exclusive an upscale district of the city, the cemetery is today a tourist attraction as well as a powerful symbolic landmark of Buenos Aires. Many of its tombs were built by well-known architects and artists whose work in the visual arts and statuary is well known. Unlike other cemeteries in Argentina, Recoleta is considered to be a small necropolis, reproducing the urban grid of the city in a miniature scale. The organization of architectonic space in the cemetery, which is based upon a grid of walkways traversed by two diagonal paths, bears an astonishing resemblance to the architectonic layout of the political and financial center of Buenos Aires, the area that surrounds the Plaza de Mayo.

Examples 5 and 6. Cemetery and Plaza de Mayo satellite view

9In this way, the cemetery forms a coherent continuum with the city landscape, and can be thought of as its architectonic echo. We can walk through its narrow ‘streets’ to contemplate the beauty of the monuments, which combine the intimate function of providing eternal rest with the typical pretension of public monuments: assertion of self importance. With a surface of more than 40 000 square meters and devoid of orienting signage, the cemetery easily becomes a labyrinth to its visitors. Tertulia tried to relate this spatial experience with history: at some point, spectators would find themselves disoriented, lost within their own history, while surrounded by sounds, voices, and images of Argentinean’s past and present. At the same time, the magnitude of the piece and its consequent unwieldiness served as an analogy for the impossibility of knowing history as a whole. There was no opportunity to listen to a ‘complete’ Tertulia, as a single and unified totality, because there was no such thing. Instead, there were thousands of fragments, simultaneous and contradicting stories, with which each visitor would compose his or her own metanarrative. History was understood not as a singular and totalized narrative, but as collective construction assembled through the combination of many different visions; Tertulia’s structure reproduced this conception of history. The spatial disposition of the chosen characters inside Tertulia made it clear to visitors that listening to the voice of one person would, in most cases, require them to stop listening to the voice of someone else. In this way, each pilgrim would listen to a unique Tertulia and build a personal view of history, incorporating into musical combinations and additional layers of interpretation produced by his or her experience of walking through the cemetery.

Music

Musical structure and global form

10Tertulia was inspired in its musical concept by the polyphony used in late 15th century compositions and the famous motets composed using forty real parts. The will to organize many different layers of information and still retain a coherent unity was brought to its extreme in the creation of this piece. The challenge was to deal with forty real voices and compose a three-hour work for each one of them. As mentioned earlier, the composition derived from each voice’s alternated selections of unaltered sound archive materials with pure electro-acoustic music that had been composed using the archival those documents as musical sources.

1) Synchronies

11Tertulia was organized by a series of seven synchronies, which worked as pillars for the formal structure. During a synchrony, the same sound, word, or musical element could be heard coming out from the forty speakers simultaneously. These structural axes organized the internal tempi of each voice or group of voices. The cemetery became an entity that spoke as a whole, and one clearly perceived the interaction between all the voices contained within it. These moments were more like symphonic passages, in contrast with the others that were more chamber-like. After every synchrony, all forty characters recovered their individual voices. The sounds that were heard during each synchrony were selected because they were relevant to all of the voices in some way. The first, which opened the piece, was comprised of bell sounds: forty different bell sounds were designed for the synchrony. Real bells, synthesized bells, low bells, mid bells, high bells, imaginary bells all sounded at different tempos, and their timbres slowly evolved in different ways during the first ten minutes of Tertulia. This worked, in a way, to call upon the spirits to rise up and talk, as an invitation from the living to dead to join in the Tertulia. The second synchrony took place twenty-six minutes after the piece began, and it consisted of a military trumpet that played a short call in unison with a Mapuche flute.8 When these two wind instruments played together Indians and their exterminators were confronted in a dialogue; amazingly, both calls were very similar in pitch and rhythm. The third synchrony was the recital of a poem by Nestor Perlongher called Cadáveres (Cadavers);9 it was heard fifteen minutes after the first hour had passed. Each of the poem’s (surprisingly) forty verses ends with the same phrase: hay cadáveres (there are dead bodies). The poem was disassembled and each of the verses was assigned to one of the voices, to be later recited in such a way that all of the final phrases resounded in unison. The fourth synchrony was the sound of a Malón.10 Based on the sound of horses’ footfalls and human shouts, the malón moved through the whole cemetery and finally dissipated. The fifth was the sound of an execution: one heard a firearm loaded and discharged three times. The sixth synchrony was a fragment of Argentina’s national anthem, as sung by children in an elementary school. The forty voices sang the last verses of the anthem as in a choir. The final synchrony also ended the work. It resembled the sound of clockwork, but it was made of forty different piano sounds that approximated the sound of bells, the sounds with which the piece had begun. Before the work ended, one could hear the voice of Jorge Luis Borges reading a fragment of his poem El Gólem: ‘Gradualmente se vio (como nosotros)/Aprisionado en esta red sonora/De Antes, Después, Ayer, Mientras, Ahora, Derecha, Izquierda, Yo, Tú, Aquellos, Otros’.11 This synchrony dissolved into the final five minutes of the work, in which the only sounds that remained were the characters’ respective elements according to alchemy: the earth rumbling, wind, water, and fire. This was a way to say farewell and to return the voices to their eternal rest after the Tertulia.

2) Raps

12All synchronies, with the exception of the first, were immediately preceded by a rap: a series of sounds that included slamming doors, keys, chains, breaking glass, chairs, and objects falling down. In parapsychology, raps are known to be the kind of sounds one hears immediately before a spirit appears. They also functioned as a kind of synchrony because all forty speakers emitted these sounds for approximately two minutes before each synchrony. Yet, at the same time, each voice was composed in relation to its proximity with the others: the rap associated with each voice was unique; it was composed as a crescendo that closed with a very fast release, which was simultaneous among the voices at the moment when they all reached the fortissimo.

3) Echoes

13Immediately after each synchrony, a fragment of its sounds echoed back to the listener. Each echo described the intersection of at least two distinct trajectories, which jumped from one voice to another and traveling throughout the cemetery. After each echo, the individual forty voices were recovered, until the next choral series of raps, synchrony and echo.

14The echo of the fifth synchrony was particularly interesting: after the three gunshots were heard, the sound of a rifle being loaded was formulated and repeated in such a way so as to resemble the sound of a clockwork mechanism. A metaphor of time, as measured by the tic-tac of a gun, accurately summarized Argentina’s history, particularly the last seventy years, during which military governments dominated the country’s political scene.

Composing and mixing criteria for local structures

15The selected voices were well distributed amidst Tertulia’s cartography. Analyzing this pattern, we find the following groupings:

-

Solos:12 we find eighteen voices that were more or less isolated.

-

Duos:13 we have four of these pairing.

-

Trios:14 Of the three trios, several were considered as a duo or as a solo voice.

-

Quartets:15 two quartets were formed; their proximity allowed them to use each other’s contaminating sounds in an interesting way.

-

Quintet:16 only one quintet was formed. It is represented in the lower left side of the map.

16These groupings were treated in different ways:

-

The solo voices were treated as soloists; they were generally composed as monophonic pieces (except for the synchronic moments).

-

Groupings of two or three voices were thought of as dialogues. In these dialogues, parallel speech or musical discourse would be composed so that, although the voices spoke at the same time, no one´s voice interrupted the others. The simultaneous materials produced a very smooth texture, in which special care was taken to produce a pleasant environment.

-

We gave the name ‘tertulias’ to the gatherings of four or five voices. These could be approached as dialogues, but they could also be scores, where each voice was composed as one part of a counterpoint, resulting in a more homogenous piece that was recognizable as a single unity. This was the case, for instance, with a minimal composition assembled from fragments of several piano pieces by Alberto Williams: each of the five voices proximate to his reproduced a particular voice within this composition, producing what was clearly a complex counterpoint music performed by the five voices. The raps also exemplified this particular criterion, but in a more concrete music style.

-

The synchronies were composed as unisons of the forty voices.

-

In some cases, especially during the echoes or the Malón, a whole zone or group of voices was mixed and treated in counterpoint in relation to another group. In these Bands, as we called them, an entire group of voices was treated as a single voice, which was set against another ‘single voice’, itself conformed by multiple voices.

Materials, Relations and Processes

17There were basically three types of sound materials used in Tertulia’s musical composition: the voices of the selected personages, music related to each voice, and sounds that could build a connection to each of the personages. The work proposed relations that were not only biographical, but also genealogical and surrealistic. The cemetery was conceived of as a virtual network in which each of the forty mausoleums were nodes a visitor could click to travel through space and time. The sound and image materials that were processed were selected based upon criteria that reflected the types of connections the work would suggest:

-

Biographical: this included not only the voice of each character, but also music related to him (such as many different versions and variations of Argentina’s national anthem, played at the composer’s tomb to honor him,) or a sound that referred to an important episode in the character’s life.

-

Genealogical: an analogy was established between the character from the past and a well-known figure (national or international) from the present, and the selected sound or image directly pertained to the contemporary personage. This comparison implied an artistic and, in many cases, ideological contextualization of the historical figure. The specific raw material was chosen after answering the question of who among the living would represent that character today? This particular kind of relation not only proposed associations with the character, but it could also link a specific event of his or her life with another analogous event of the recent past. These genealogical relations also function backwards by proposing a connection between an individual from recent history who is buried in Recoleta with an event or character from the beginning of the 19th century.

-

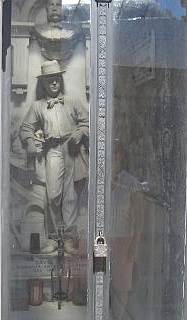

Surrealistic: the characters and sound materials were also related to each other based on more open criteria that produced intriguing and even humorous connections. For instance, in the tomb of General Sarmiento17 (who died on September 11th, 1888), one could find images of the 9-11 Twin Towers attack and images of the military coup that ousted Salvador Allende’s government in Chile, which took place on September 11th of 1973. Another example was Ramón Falcón’s18 tomb, for which a short work was composed using the voice of Don Ramón (a character from Mexican TV show El Chavo del Ocho).19

-

Alchemic: because Tertulia involved so many different characters, we needed to find a common characteristic among them in order to maintain the work’s overall coherence. It eventually became clear that the one thing all the characters had in common was the fact that they were all dead. Therefore, the supernatural was introduced as key figure in the work and a common referent among the characters: the four elements of nature appeared in sounds and images that referred to each character’s date of birth. The images used in Tertulia also resembled images on Tarot cards (of which there are forty in a deck). In the upper right corner of each of the images one could find a figure holding a vase; the vase bore the sign of the element (earth, fire, water, or air) that corresponded with the birthdate of the person in question. Included in the lower left corner of each image was a representation of hell, heaven or purgatory (taken from Durer’s engravings for Dante’s Divina Comedia), or an erotic image.

Example 7. Image for Facundo Quiroga’s tomb

1. The voice

181.1 Among the source materials we considered using for the musical compositions, highest preference was given to recordings of the actual voices of the characters, when these materials were available. But our research on mid-century Argentinean cinema (specially from the nineteen-forties and fifties) led us to include in the works voices of actors representing the historical characters in question. We did this most often with the compositions for which no recording of the original voice was available (which was obviously the case with characters from the 19th century and earlier.) We also considered as possible sources the voices of other people talking about the historical character. For example, a visitor to Evita’s grave could listen to Rodolfo Walsh’s20 voice reading Esa Mujer (That Woman), his acclaimed short story (which was based on actual facts), about the fate of Evita’s body after her death.21 We selected many other types of voices in order to produce the genealogical and surrealistic associations described above. For example, a visitor to the tomb of Dominguito, the adopted son of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, heard a digitally-generated voice recite a text about the founding of a freemasonry society that counted among its members many of Argentina’s forefathers.

191.2 Our treatment of all of the voices can be described by the following five processes:22

-

The document remained unaltered, with the exception of restoration the original sound file might have required. These unaltered recordings were incorporated into many of the three-hour long compositions.

-

The original voice underwent a series of cut and paste operations that isolated a particular phrase, word, or sentence that was then manipulated like, and combined with, electronic sounds, which were often generated from the same original recording.

-

The original voice was digitally processed in such a way that its speaker ceased to be recognizable, which created a passage much closer to traditional electro acoustic music.

-

The voice underwent a series of cut and paste operations of a very particular kind. For example, in Luis Vernet’s tomb, who was the last governor of Malvinas (the Falkland Islands) before the islands were illegitimately invaded by Great Britain in 1822, one composition combined the voice of Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri with the voice of Margaret Thatcher giving a speech to the House of Lords on April 1st, 1982. A surgical operation was performed on Thatcher’s speech in the following way: first a brief sentence was isolated (taking into account breath pauses and intonation); each word in the sentence was divided into its component syllables or clearest minimal sound objects (these were multisyllabic in some cases when the voice’s inflections ran one syllable into the next). Finally, these tiny word fragments were assembled in reverse order: the passage opened with the last syllable of the last word of the first sentence fragment. Immediately after a very brief silence (generally one second or less); the penultimate syllable was added, so that one heard the final two syllables together in their original order; a third syllable was added in the same way (and perhaps a word was already intelligible at this point), and so on until that first sentence was completed. Then the same procedure was repeated in its entirety with the next isolated phrase or sentence. The parliament’s endorsement of Thatcher’s speech, functions as a litany or ostinato in the composition: under the Prime Minister’s voice we hear a chorus of voices rhythmically repeating ‘yeah…, yeah…’, until they are finally transformed into the sounds of the sea and waves breaking on a shore.

-

A unique operation was performed on Eva Peron’s films: Eva’s voice was extracted from each film’s dialogue; her isolated lines of dialogue were then assembled into a continuous monologue that simulated a single, long sentence. The result was a strange (and even humorous) discourse in which questions were left unanswered and interpellations received no responses, revealing how the movie scripts were interlaced with subtle propaganda for the Peronism.

2. The music

202.1 The source materials for Tertulia included many different kinds of music Because most of the chosen characters were of historic importance, we included many anthems, hymns, and songs from marches that had been composed to celebrate these figures. But the sources also included music from the Montoneros’23 clandestine radio transmissions of the 1970s (whose style was a fusion of folk and rock), a composition featured in a documentary about the Spanish Civil War, Alberto Williams’s24 piano compositions, old tangos, propaganda music, and the theme songs Martín Karadagian25 composed for the wrestlers that appeared on the television show Ring Titans.

212.2 The musical sources were altered by the following processes:

-

The music suffered no transformation at all, except for restoration or sectional fragmentation. In these cases, the raw document was heard without the effects of any processing.

-

The music was cut and sampled, so that the original work became material for new music compositions that used collage techniques.

-

The music was used for an electro acoustic composition in which the original music was arranged or freely adapted to make a new version. This was how most of the music that was originally composed to celebrate a historic figure was processed, including Argentina’s national anthem.

-

Music was also composed using no source at all. This was the case for many of the sections of the Peristilo26, in which passages were composed based upon the idea of an orchestra tuning before a concert.

3. The sounds

223.1 Of the myriad sounds that were used, these are among the most important:

-

Natural sounds: in accord with the references to alchemy that appeared in

-

Tertulia’s images (discussed in section IV d), the sounds of fire, water, wind, and earth (rumbling) functioned as wildcard sounds, to fill in gaps between more musically organized passages, and also as layers within certain compositions.

-

War sounds: Tertulia’s visitors heard the sounds of gunshots, bombs, tanks, swords, and cannons, as well as those of other weapons and horns. Because these were recognizable as sounds of warfare, yet their specific provenance was ambiguous, the war sounds were able to link together many of the characters in Tertulia, given that nearly all of the selected personages had been involved in military or guerilla warfare, or violent military coups.

-

Urban sounds: cars, trains, motorcycles, street ambiences, radio static, crowd cheering, helicopters, etc.

-

Miscellaneous: doors, chains, keys, chairs, glass crashing, objects rattling or tumbling down. These sounds were mostly used in the Raps, discussed above.

233.2 Sound processing: three degrees of transformations were applied to audio source material:

-

A low level of processing that allowed the original sound to remain recognizable.

-

A more powerful process that produced a sound whose reference was ambiguous.

-

An extreme process that erased all reference to the original source.

Exceptional roles

24There were a few voices that underwent a unique treatment. This was the case for the voice of David Alleno (number 25), who was the keeper of the cemetery for many years. According to urban myth, he worked in the Recoleta cemetery until he had saved enough money to buy his own grave on its grounds, then promptly killed himself. In his tomb one can see a statue of Alleno with his dog, a bucket, a broom, and the keys of the cemetery (Example 8. David Alleno’s grave). He was a very important character within the intervention: he had the keys to the Tertulia. Alleno’s voice was composed with the sounds of his character’s known attributes: the sounds of keys twinkling, a dog walking, and footsteps. His was the only voice that circulated continuously throughout the whole cemetery: it could be heard briefly and unexpectedly in any of the other speakers, as if Alleno were walking through and tending to the cemetery. Metaphorically, his character also connected the worlds of the living and the dead.

25Another unique treatment was given to the voice of Julia Selma Ocampo. She was kidnapped and killed by Argentina’s last military government (1976-1983), and the sign on her grave states: ‘The body of Julia Selma Ocampo is missing, and we haven´t heard anything of her since 1977’. Her voice was a three-hour silence that was broken only once. In this brief moment one heard the voice of Nestor Perlongher reading the last verse of his poem ‘Cadáveres.’ Immediately after the synchrony in which ‘There are cadavers,’ resounded throughout the cemetery, Perlongher’s voice broke the silence of Ocampo’s tomb with the poem’s final verse: ‘cadavers, cadavers, cadavers… (knock knock knock knock) there’s no one there? – Asks the woman from Paraguay – Answer: there are no cadavers.’ The image Molinari created for Ocampo’s grave was a lightbox with no images: just a surface of white light. Selma Ocampo’s grave was the final stop on the tour we suggested to visitors of Tertulia. There were no speakers in the last corridor one passed through before leaving the cemetery; it was intended a moment of silence…

Example 8. David Alleno’s grave

26The experience of working collaboratively to assemble Tertulia’s various components – sound, image, narrative, spatial layout – into a coherent work recalls the experience of theatrical production. The Tertulia itself also had theatrical resonances, with its cast of characters and the roles they each had within the work’s structure. Alberto Williams, a composer from the early twentieth century, was the piano man of the night; his piano pieces were used as his exclusive material. As stated above, Alleno was the gatekeeper; he had the keys to move between the worlds of the living and the dead. Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson was the event’s hostess because she organized very famous tertulias in the nineteenth century where guests discussed culture and politics, and danced and dined on traditional dishes. The first performance of Argentina´s national anthem took place at her home. Ramón L. Falcón was in charge of the security of the evening. Sarmiento was the very important person that everybody hoped to meet. Facundo Quiroga was the first person visitors met when they entered Tertulia, a curious welcome for such an aristocratic site, given that Quiroga represented barbaric Argentina.

The team

27The team that created Tertulia was organized as a film production team would be. It was divided into a Sound Department and an Image Department. The fifteen collaborators included a filmmaker, a poet, a historian, a philosopher, a sound designer, playwright, four composers, three visual artists, a lighting designer, and an art historian.

28I composed the music in collaboration with two other composers, Pablo Chimenti and Hernán Kelleñevich. They worked as a second unit of composition (similar to the second units in film production); they were responsible for voices and entire sections of the compositions. Without their talent and dedication, Tertulia would have never been made. And the same can be said of the other members of the crew: Eduardo Molinari, Julián D’Angiolillo, Daniel Hernández, Matías Sendón, Laura Guzik, Juan Pablo Gómez, Nicolás Arispe, Cristian Forte, Claudio ‘Toro’ Martínez, Gabriel Castillo and Gabriel Di Meglio. I would like to express my sincere admiration for all of them, and my deepest thanks.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Jennifer Flores Sternad and Teresa Riccardi who were kind enough to read and correct this article. All photographs by Julián D’Angiolilloexcepted example 7 by Eduardo Molinari. Satellite photos by Google Earth.

Notes

1 These not-able personalities included a former Argentinean ambassador to Great Britian, who served as ambassador during the dictatorship of Leopoldo Galtieri (1981-1982); the daughter of Roberto M. Levingston, dictator from 1970–71; and Juan Carlos Cresto, who, at the time, was director of Argentina’s National Museum of History, but was removed from that position soon after Tertulia took place. Surprisingly, a historian (someone who dialogues with the dead) objected to a project that dealt with the past, and collective and individual memory.

2 Escuela Terciaria de Estudios Radiofónicos is a private school for the study of radio communication and journalism. Eduardo Aliverti, to whom Tertulia is very grateful, directs it.

3 P.A.I.S. (Project Art In Situ : a musical narrative of space, sound and oral speech) is a research project based at the University of Quilmes, and is part of the Programa Pioritario de Investigación Teatro Acústico (Acoustic Theatre Research Program), directed by composer Oscar Edelstein.

4 Roland Barthes, Image Music Text, New York, Hill and Wang, 1998.

5 For additional discussion of this matter, please see Trevor Wishart’s On sonic art, Amsterdam, Harwood Academic Publishers, Simon Emerson, 1996.

6 Carl Dahlhaus addresses this idea in La idea de la música absoluta, Barcelona, Idea Books, 1999.

7 Frances A. Yates discusses memory locus in The Art of Memory, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, Paperback edition, 1974. P.A.I.S. thinks of public spaces as memory loci, where each site’s history, its present and past social functions, and its architectonic and acoustic characteristics can be incorporated into a subjective experience of the site, as musical parameters that modify perception of sound.

8 The Mapuches are one of the native peoples that lived in the south of Argentina before the Spanish arrived in the Americas.

9 The poem refers directly to the desaparecidos (disappeared people) : people who were illegally imprisoned, tortured, and murdered by the last military regime in Argentina (1976-1983). The bodies from the desaparecidos were never found : some of them where buried in unmarked graves and many where thrown into Buenos Aires’s river, the Río de La Plata.

10 Malón is the name given to the raids carried out by the indigenous people in the south of Argentina against the military camps and civilian town that were situated on the border of Patagonia and the central part of the country. As a result of the Desert Campaign, which was conducted by general Roca, the indigenous people were exterminated and Patagonia became part of Argentina.

11 Gradually he saw himself (like us) / trapped in this sonorous web / of Before, After, Yesterday, While, Now / Right, Left, Me, You, Those, Us.

12 The Solos : 01_Quiroga, 06_Palacios, 07_Dominguito, 12_Radicales 13_Firpo, 21_Falcón, 24_Hernández, 25_Alleno, 26_Sáenz Peña, 27_Vernet, 28, López y Planes, 29_Evita, 30_Karadagián, 31_Rufina, 32_Sarmiento, 37_Selma Ocampo, 39_Remanso, 40_Peristilo

13 The Duos : 08_Alberdi + 09_Rosas ; 10_Lavalle + 11_Lonardi ; 19_Macedonio + 20_Girondo ; 22_Paraguay+23 Uriburu.

14 22_Paraguay + 23_Uriburu + 26_Sáenz Peña, 19_Macedonio + 20_Girondo + 18_Roca.

15 The Quartets : 02_Dorrego + 03_Saavedra + 04_Mariquita + 05_Remedios ; 14_Mosconi + 15_Quijada + 16 Pellegrini + 17 Aramburu.

16 The Quintet : 33_Szaszak + 34_Mitre + 35_Williams + 36_Alzaga + 37_Borges.

17 Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Argentina’s president from 1868-1874, is one of the most important intellectuals and politicians in the country’s history. He was a champion for education, and when he died, in honor of Sarmiento’s memory, the date of his death was declared a national holiday : teacher’s day. Sarmiento is credited as being the first to propose the dichotomy of civilization and barbarism to describe Argentinean society.

18 Ramón L. Falcón was the chief of police in Buenos Aires during the first decade of the twentieth century, when the city’s workers suffered under his harsh and repressive politics. Falcón was responsible for the massacre of hundreds of workers during an anarchist demonstration. In 1909 anarchist Simón Radowisztky used a homemade bomb to kill Falcón as the police chief was taking a ride in his carriage.

19 Rodolfo Pérez Bolaños is a Mexican comedian who wrote and starred in the television series El Chavo del ocho. In the series, Chavo, an eight year-old orphan, lives in the same neighborhood as Don Ramón. The quicktempered Don Ramón is known for treating Chavo with particular unkindness.

20 Rodolfo Walsh (19…-1977) was an intellectual and writer politically engaged with peronism’s left armed wing Montoneros. His style was a mixture of literature, historic research and journalism. Its aesthetic position is very close to Tertulia, in the way he approached documents as sources for his literature.

21 Evita Peron died of cancer in 1952. Her body was mummified by Peron and kidnapped after the military coup that separated him from the presidency in 1955. Her body was raped and suffered a series of mutilations ; and it was secretly taken out of the country to find eternal rest finally at the Recoleta cemetery 30 years ago.

22 The voice of almost every character was treated with all of these processes during the course of its three-hour audio stream.

23 The Montoneros’ first military operation was the kidnapping of General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, whose presidency immediately followed Perón’s deposition. They intended to use their hostage to recover the body of Eva Peron, which still missing at the time. Aramburu was finally executed after a revolutionary trial. The bodies of both Eva Perón and Aramburu are buried in Recoleta.

24 Alberto Williams was an Argentinian composer from the early twentieth century who found inspiration for many of his compositions in the country’s folk rhythms.

25 Martín Karadagian was a professional wrestler who had a television show called Ring Titans (Titanes en el ring). The popular program aired for long enough to be enjoyed by three generations. Each of the “titans” appeared on the show in a unique costume and accompanied by a personal theme song that described the attributes of his character.

26 The Persitilo is the main space in the entrance to the cemetery. Of the forty individual sites within the cemetery in which we intervened, the Peristilo and the Compass (Brújula) were the only two that were not graves. The Compass functioned as a complex orientation device : a table was positioned at the crossroads of several of the cemetery’s walkways, and the varied images laid out upon it were organized in relation to the cardinal directions.

Citation

Auteur

Quelques mots à propos de : Nicolás Varchausky